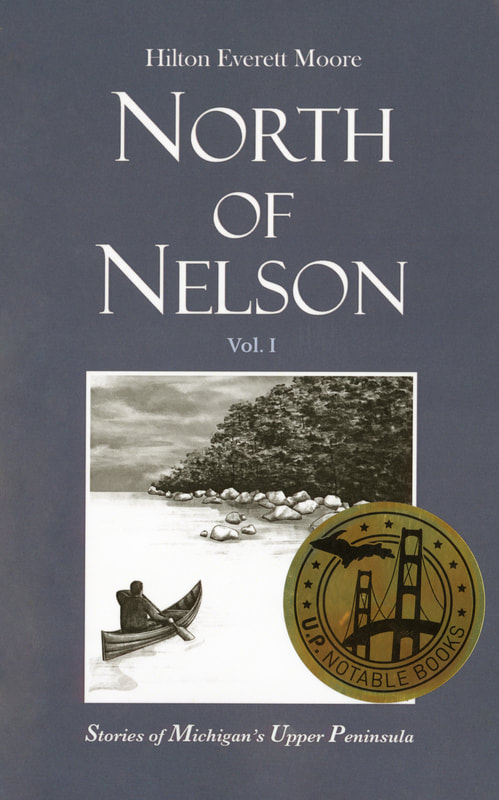

"North of Nelson, Volume I"

A published nostalgic collection of six short stories has been completed and is in distribution by Silver Mountain Press. Email [email protected] for your copy.

"The Silent Mistress"

My short story, "The Silent Mistress" was named Editor's Choice in the fall 2020 edition of Euphemism's online magazine published by Illinois State University.

Read the story for free at the website listed below:

english.illinoisstate.edu/euphemism/16-1/

"Requiem for Ernie" and "A Dog Named Bunny"

As is "The Silent Mistress", the above titles are two short stories from my novel, "North of Nelson, Volume I" and are now in print by UP Reader. You can get your own copy by emailing [email protected]

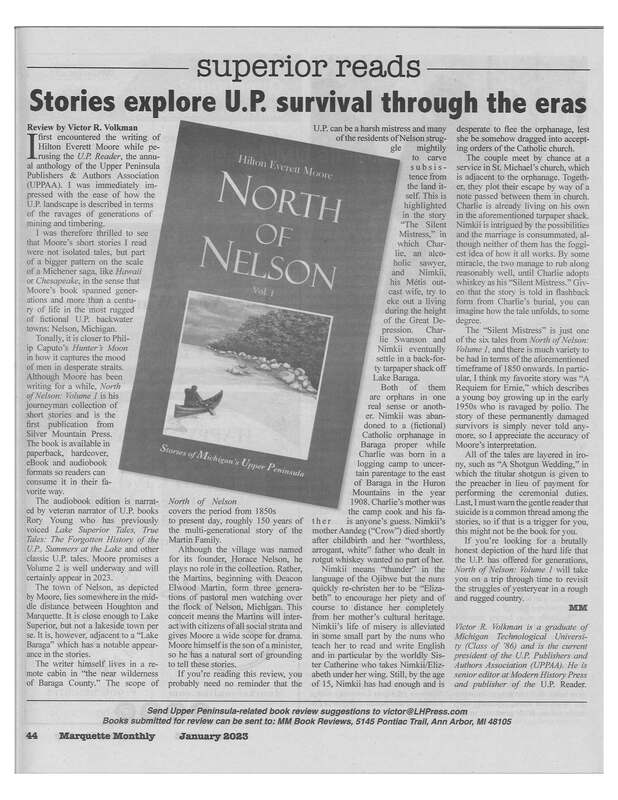

Here is an early review of my short story collection, "North of Nelson, Volume I". It was published in the January issue of the "Marquette Monthly". May this inspire you to read the collection for yourself. You can get your copy by contacting me as shown below.

North of Nelson, Volume I has also been named one of the top ten in the January, 2023, 4th Annual U.P. Notable Book Awards by a jury from the Upper Peninsula Publishers and Authors Association, (UPPAA). You can check this out at:

https://www.uppaa.org/2023/01/02/u-p-notable-books-list-honors-the-years-best-u-p-authors-and-their-books/

FOR MORE INFORMATION CONTACT THE AUTHOR at: [email protected].

North of Nelson, Volume I awarded One of the Top Ten U.P. Notable Books